- Home

- Woody Guthrie

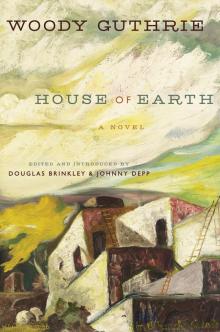

House of Earth

House of Earth Read online

HOUSE OF EARTH

A NOVEL

WOODY GUTHRIE

Edited and Introduced by

Douglas Brinkley and Johnny Depp

DEDICATION

TO

Nora Guthrie

AND

Tiffany Colannino

AND

Guy Logsdon

EPIGRAPH

I ain’t seen my family in twenty years

That ain’t easy to understand

They may be dead by now

I lost track of them after they lost their land

—BOB DYLAN, “Long and Wasted Years”

And seeing the multitudes, he went up into a mountain: and when he was set, his disciples came unto him:

And he opened his mouth, and taught them, saying,

Blessed are the poor in spirit: for theirs is the kingdom of heaven.

Blessed are they that mourn: for they shall be comforted.

Blessed are the meek: for they shall inherit the earth.

—MATTHEW 5:1–5 (King James Version)

CONTENTS

Dedication

Epigraph

Introduction

I DRY ROSIN

II TERMITES

III AUCTION BLOCK

IV HAMMER RING

Acknowledgments

Selected Bibliography

Selected Discography

Biographical Time Line

About the Author

Credits

Copyright

About the Publisher

INTRODUCTION

Life’s pretty tough. . . . You’re lucky if

you live through it.

—WOODY GUTHRIE

1

On Sunday, April 14, 1935—Palm Sunday—the itinerant sign painter and folksinger Woody Guthrie thought the apocalypse was knockin’ on the door of Pampa, Texas. An immense dust cloud—one that had emanated from the Dakotas—swept grimly across the Panhandle, like the Black Hills on wheels, blotting out sky and sun. As the dust storm approached the town, the bright afternoon was eclipsed by an ominous darkness. Fear engulfed the community. Had its doom arrived? No one in Pampa was safe from this beast. Huddled around a lone lightbulb in a shabby, makeshift wooden house with family and friends, Guthrie, a Christian believer, prayed for survival. The demented winds fingered their way through the loose-fitting windows, cracked walls, and wooden doors of the house. The people in Guthrie’s tight quarters held wet rags over their mouths, desperate to keep the swirling dust from asphyxiating them. Breathing even shallowly and irregularly was an exercise in forbearance. Guthrie, eyes shut tight, face firm, kept coughing and spitting mud.

What Guthrie experienced in Pampa, a vortex in the Dust Bowl, he said, was like “the Red Sea closing in on the Israel children.” According to Guthrie, for three hours that April afternoon a terrified Pampan couldn’t see a “dime in his pocket, the shirt on your back, or the meal on your table, not a dadgum thing.” When the dust storm finally passed, locals shoveled dirt from their front porches and swept basketfuls of debris from inside their houses. Guthrie, incessantly curious, tried to reconcile the joy of being alive with the widespread despair. He surveyed the damage in Pampa the way a veteran reporter would have done. The engines of the usually reliable G.M. motorcars and Fordson tractors had been ruined by thick grime. Huge dunes had accumulated in corrals and alongside wooden ranch homes. Most of the livestock had perished in the storm, the sand clogging their throats and noses. Even vultures hadn’t survived the maelstrom. Images of human anguish were everywhere. Some old people, hit the hardest, had suffered permanent damage to their eyes and lungs. “Dust pneumonia,” as physicians called the many cases of debilitating respiratory illness, became an epidemic in the Texas Panhandle. Guthrie would later write a song about it.

To express his sympathy for the survivors of that Palm Sunday, Guthrie wrote a powerful lament, which set the tone and tenor of his career as a Dust Bowl balladeer:

On the fourteenth day of April,

Of nineteen thirty-five,

There struck the worst of dust storms

That ever filled the sky.

You could see that dust storm coming

It looked so awful black,

And through our little city,

It left a dreadful track.

In the spring of 1935, Pampa was not the only town that had been punished by the agony and losses of the four-year drought. Sudden dust cyclones—black, gray, brown, and red—had also ravaged the high, dry plains of Kansas, Nebraska, Oklahoma, Arkansas, Texas, Colorado, and New Mexico. Still, nothing had prepared the region’s farmers, ranchers, day laborers, and boomers for the Palm Sunday when a huge black blob and dozens of other, smaller dust clouds quickly developed into one of the worst ecological disasters in history. Vegetation and wildlife were destroyed far and wide. By summer, the hot winds had sucked up millions of bushels of topsoil, and the continuing drought devastated agriculture in the lowlands. Poor tenant farmers became even poorer because their fields were barren. Throughout the Great Depression, the Great Plains underwent intolerable torment. The prolonged drought of the early 1930s had destroyed crops, eroded land, and caused many deaths. Thousands of tons of dark topsoil, mixed with red clay, had been blown down to Texas from the Dakotas and Nebraska, carried by winds of fifty to seventy miles per hour. A sense of hopelessness prevailed. But the indefatigable Guthrie, a documentarian at heart, decided that writing folk songs would be a heroic way to lift the sagging morale of the people.

Confronted with dreariness and absurdity, with poor folks in distress, many of them financially ruined by the Dust Bowl, Guthrie turned philosophical. There had to be a better way of living than in rickety wooden lean-tos that warped in the summer humidity, were vulnerable to termite infestation, lacked insulation in subzero winter weather, and blew away in a sandstorm or a snow blizzard. Guthrie realized that his neighbors needed three things to survive the Depression: food, water, and shelter. He decided to concern himself with the third in his only fully realized novel: the poignant House of Earth.

A central premise of House of Earth—first conceived in the late 1930s but not fully composed until 1947—is that “wood rots.” At one point in Guthrie’s narrative, there is a tirade against forestry products that rot down … sway … keel over. Someone curses at a wooden home: “Die! Fall! Rot!” Scarred by the dust storm of April 14, Guthrie, a socialist, damned Big Agriculture and capitalism for the degradation of the land. If there is an overall ethos in House of Earth, it’s that those with power—especially Big Banks, Big Lumber, Big Agriculture—should be chastised as repugnant robber barons and rejected by wage earners. Woody was a union man. But his harangues against the powers that be are also tinged with self-doubt. Can one person really fight against wind, dust, and snow? Isn’t venting one’s spleen futile in the end?

Scholars who devote themselves to Woody Guthrie are continually amazed by how much unpublished work the Oklahoma troubadour left behind. He had an unerring instinct for social justice, and he was a veritable writing machine. During his fifty-five years of life, he wrote scores of journals, diaries, and letters. He often illustrated them with good-hearted cartoons, watercolor sketches, and comical stickers. Then there are the memoirs and his more than three thousand song lyrics. He regularly scribbled random ideas on newspapers and paper towels. And he was no slouch when it came to art. But House of Earth—in which wood is a metaphor for capitalist plunderers while adobe represents a socialist utopia where tenant farmers own land—is Guthrie’s only accomplished novel. The book is a call to arms in the same vein as the best ballads in his Dust Bowl catalog.

The setting for House of Earth is the mostly treeless, arid Caprock country of the Texas Panhandle near Pampa. T

his was Guthrie’s hard-luck country. He was proud that the Great Plains were his ancestral home. It’s perhaps surprising to realize that Guthrie of Oklahoma—who tramped from the redwoods of California to subtropical Florida throughout his storied career—first developed his distinctive writing style in the windswept Texas Panhandle. Guthrie’s treasured Caprock escarpment forms a geological boundary between the High Plains to the east and the Lower Plains of West Texas. The soils in the region were dark brown to reddish-brown sand, sandy loams, and clay loams. They made for wonderful farming. But the lack of shelterbelts—except the Cross Timbers, a narrow band of blackjack and post oak running southward from Oklahoma to Central Texas between meridians 96 and 99—left crops vulnerable to the deadly winds. Soil erosion became a plague, owing to misuse of the land by Big Agriculture, an entity that Guthrie wickedly skewers in the novel.

Guthrie, it seems, knew more about the Caprock country than perhaps any other creative artist who ever lived. He knew the local slang and the idioms of the Panhandle region, the secret hideaways, and the best fishing holes. Throughout House of Earth, Guthrie uses speech patterns (“or something like that”; “shore cain’t”; and “I wish’t I could”) with sure command. Exclamations such as “Whooooo” and “Lookkky!” help establish Guthrie’s populist credibility. He had lived with people very similar to the novel’s hardscrabble characters. His slang expressions are lures similar to those found in O. Henry’s folksy short stories. Building on Will Rogers’s large comedy repertoire, Guthrie, in a little pamphlet titled $30 Wood Help, gave a thumbnail impression of his beloved Lone Star State while carping about the lumber barons turned loan sharks. “Texas,” he wrote, “is where you can see further, see less, walk further, eat less, hitch hike further and travel less, see more cows and less milk, more trees and less shade, more rivers and less water, and have more fun on less money than anywhere else.”

House of Earth has a literary staying power that makes it more than just a curiosity: homespun authenticity, deep-seated purpose, and folk traditions are all apparent in these pages. Guthrie clearly knows the land and the marginalized people of the Lower Plains. In the novel, he draws portraits of four hard-luck characters all recognizable, or partly recognizable, to readers familiar with his songbook: the dutiful tenant farmer “Tike” Hamlin; his feisty pregnant wife, Ella May; a nameless inspector from the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) who asks farmers to slaughter their livestock to raise farm prices; and Blanche, a registered nurse. When Tike, full of discord, lashes out at his own ramshackle house—“Die! Fall! Rot!”—he is speaking for all of the world’s poor living in squalor. Like all of Guthrie’s work, which is often erroneously pigeonholed as mere Americana, this book is a direct appeal for world governments to help the hardest-hit victims of natural disasters create new and better lives for themselves. Guthrie contrives to let his readers know in subtle ways that capitalism is the real villain in the Great Depression. It’s reasonable to say that Guthrie's novel could just as easily have been set in a Haitian shantytown or a Sudanese refugee camp as in Texas.

2

It was desperation that first brought Guthrie to forlorn Pampa. He had been born on July 14, 1912, in Okemah, Oklahoma, but in 1927, after Woody’s mother was sent to Central State Hospital for the Insane in Norman (for what today would be diagnosed as Huntington’s disease), his father moved to the Texas Panhandle. Not only were the crops withered in the Oklahoma fields during the 1920s, but the oil fields were also drying up. Tragedy seemed to follow young Woody around like a thundercloud: his older sister, Clara, died in a fire in 1919; then a decade later the Great Depression hit the Great Plains hard, bringing widespread poverty and further dislocation. After spending much of his teens scraping out an existence in Oklahoma, Woody decided in 1929 to join his father in Pampa, a far-flung community in the Texas Panhandle populated largely by cowboys, merchants, itinerant day laborers, and farmers. The mostly self-educated Woody, who had taken to playing the guitar and harmonica for a living, married a Pampa girl, Mary Jennings, who was the younger sister of a friend, the musician Matt Jennings. They would have three children. An oil discovery in the mid-1920s unexpectedly turned Pampa into a boomtown. The Guthries ran a boardinghouse, hoping to capitalize on the prosperity.

Temperamentally unsuited to a sunup-to-sundown job, Guthrie—a slight man weighing only 125 pounds—played a handsome mandolin for tips or sandwiches in every dark juke joint, dance hall, cantina, gin mill, and tequilería from Amarillo to Tucumcari. Leftist and progressive-minded, Guthrie was determined not to let poverty beat him down. He considered himself a straight-talking advocate for truth and love like Will Rogers. With head cocked and chin up, he embodied the authentic West Texas drifter complaining about how rotten life was for the poor. He became a singing spokesman for the impoverished, the debt-ridden, and the socially ostracized. Comic absurdity, however, infused everything Guthrie did. “We played for rodeos, centennials, carnivals, parades, fairs, just bustdown parties,” Guthrie recalled, “and played several nights and days a week just to hear our own boards rattle and our strings roar around in the wind.”

Determined to be a good father to his first daughter, Gwendolyn, Guthrie tried to earn an honest living in Pampa. But he was restless and broke. For extra money, he painted signs for the local C and C Market. When not making music or drawing, he holed up in the Pampa Public Library; the librarian there said he had a voracious appetite for books. Longing to grapple with life’s biggest questions, he joined the Baptist church, studied faith healing and fortune-telling, read Rosicrucian tracts, and dabbled in Eastern philosophy. He opened for business as a psychic in hopes of helping locals with their personal problems. He wanted to be a fulfiller of dreams. His music, grounded in his dedication to improving the lives of the downtrodden, was sometimes broadcast on weekends from a shoe box–size radio station in Pampa. Depending on his mood at any moment, he could be a cornpone comedian or a profound country philosopher of the airwaves. But he was always pure Woody.

His tramps around Texas took him south to the Permian basin, east to the Houston-Galveston area, then up through the Brazos valley into the North Central Plains, and back to the oil fields around Pampa. Always pulling for the underdog, the footloose Guthrie lived in hobo camps, using his meager earnings to buy meals or to shower. He was proud to be part of the downtrodden of the southern zone. His heart swelled with his new social consciousness:

If I was President Roosevelt

I’d make groceries free—

I’d give away new Stetson hats,

And let the whiskey be.

I’d pass out suits of clothing

At least three times a week—

And shoot the first big oil man

That killed the fishing creek.

It was while busking around New Mexico that Guthrie’s gospel of adobe took root. In December 1936, nineteen months after the Black Sunday when the dust storm terrorized the Texas Panhandle, Guthrie had an epiphany. In Santa Fe he visited a Nambé pueblo on the outskirts of town. The mud-daubed adobe walls fascinated him (as they had D. H. Lawrence and Georgia O’Keeffe). The adobe haciendas had hardy wooden rainspouts and bricks of soil and straw that were simple yet perfectly weatherproof, unlike most of the homes of his Texas friends, which were poorly constructed with scrap lumber and cheap nails. These New Mexico adobe homes, with their mud bricks (ten inches wide, fourteen inches long, and four inches high) baked in the sun, Guthrie understood, were built to last the ages.

Adobe was one of the first building materials ever used by man. Guthrie believed that Jesus Christ—his savior—was born in an adobe manger. Such structures seemed to signify Mother Earth herself. If the people in towns like Pampa were going to survive dust storms and snow blizzards, Guthrie decided, they would have to build Nambé-style homes that would stand stoutly until the Second Coming of Christ. In New Mexico, with almost religious zeal, he started painting adobes of “open air, clay, and sky.” In front of the Santa Fe Art Museum one a

fternoon, an old woman told Guthrie, “The world is made of adobe.” He was transfixed by her comment but managed to nod his head in agreement and reply, “So is man.”

Out of these epiphanies in New Mexico was born the central premise of House of Earth. To Guthrie, New Mexico, the Land of Enchantment, was a crossroads of Hispanic, Native American, African American, Asian, and European cultures. He thought of the state as a mosaic of enduring peoples and cultures. Taos Pueblo—some of its structures as much as five stories high—had been occupied by Native Americans without interruption for a millennium. Santa Fe, founded in 1610, was the first and longest-lasting European capital on US soil. As Guthrie wrote in his song “Bling Blang”—which he recorded for his 1956 album Songs to Grow On for Mother and Child—his day of reckoning, with regard to New Mexico–style adobe, was fast approaching.

I’ll grab some mud and you grab some clay

So when it rains it won’t wash away.

We’ll build a house that’ll be so strong,

The winds will sing my baby a song.

From his inquiries in New Mexico, Guthrie learned that you didn’t have to be a trained mason to build an adobe home. His dream was to live and wander in the Texas Panhandle, and to build a lasting adobe sanctuary on the ranch land he could return to at any time—one that wasn’t a wooden coffin or owned by a bank or vulnerable to the dreaded dust and snow. With the well-reasoned conviction, Guthrie, voice of the rain-starved Dust Bowl, started preaching back in Texas about the utilitarian value of adobe. For five cents, he purchased from the USDA its Bulletin No. 1720, The Use of Adobe or Sun-Dried Brick for Farm Building. Written by T. A. H. Miller, this how-to manual taught poor rural folks (among others) how to build an adobe from the cellar up. In the Panhandle, there was no cheap lumber or stone available, so adobe was the best bet for architecturally sound homes in the Southwest. All an amateur needed was a homemade mixture of clay loam and straw, which helped the brick to dry and shrink as a unit. Constructing a leakproof roof was really the only difficult part. (Emulsified asphalt was eventually used to seal the roofs of adobes.) The rest was as easy as playing tic-tac-toe.

House of Earth

House of Earth